According To The variety When you think of the great actors (Brando, Streep, De Niro, Ullmann, Day-Lewis), one of the first qualities that leaps to mind is range. Robert Duvall, who died Sunday at 95 and was most assuredly one of the great actors, had that quality to the nth degree. He was a sly-dog virtuoso whose roster of indelible characters included a broken-down country singer, a Mafia consigliere, a charismatic Pentecostal preacher, a psychotic Army commander, a corrupt TV news executive and a creepy neighbor who lives in the shadows, not to mention a whole lot of cowboys and also Dwight D. Eisenhower and Joseph Stalin. Born in California and raised in Maryland, Duvall, as much or more than any actor of his time, had a deep identification with the world of the South. In one role after another, he used a drawl and a laidback cadence to portray men from that region — both charmers and killers, each subtly different from the last, chiseling every character with a jeweler’s precision. Yet when I think of the range that Duvall expressed in his acting, I don’t simply mean his chameleonic quality. I’m talking about something more primal and emotional — the way that he navigated the light and dark sides of experience with an alternating current of quietude and fury, tenderness and violence. His characters could be loving…or brutish. Gentle…or murderous. And — this was the spice in his gumbo — sometimes both at once. It’s no exaggeration to say that Duvall’s acting career added up to an exploration of the duality of all of us.

He first came to people’s attention as Boo Radley, the mysterious recluse in the 1962 film adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” The duality was already there, in the way that everyone around him thought Boo was a monster, but he turned out to be a protector. Duvall came from the stage and did a lot of television work in the ’60s, but after making his mark in “M*A*S*H” (as the uptight soldier beau of “Hot Lips” Houlihan), he took on a role that became defining: Tom Hagen, the dutiful, trusted Irish-German lawyer and counselor to the Corleone family in “The Godfather” and its sequel. Though part of a crime syndicate, Duvall’s Hagen had qualities that seemed both corporate and priestly: a calm sense of rectitude and loyalty, along with an eerie ability to fade into the woodwork when necessary. The performance was so convincing that it was hard, at that point, not to look at Duvall and assume that those qualities defined him as an actor.

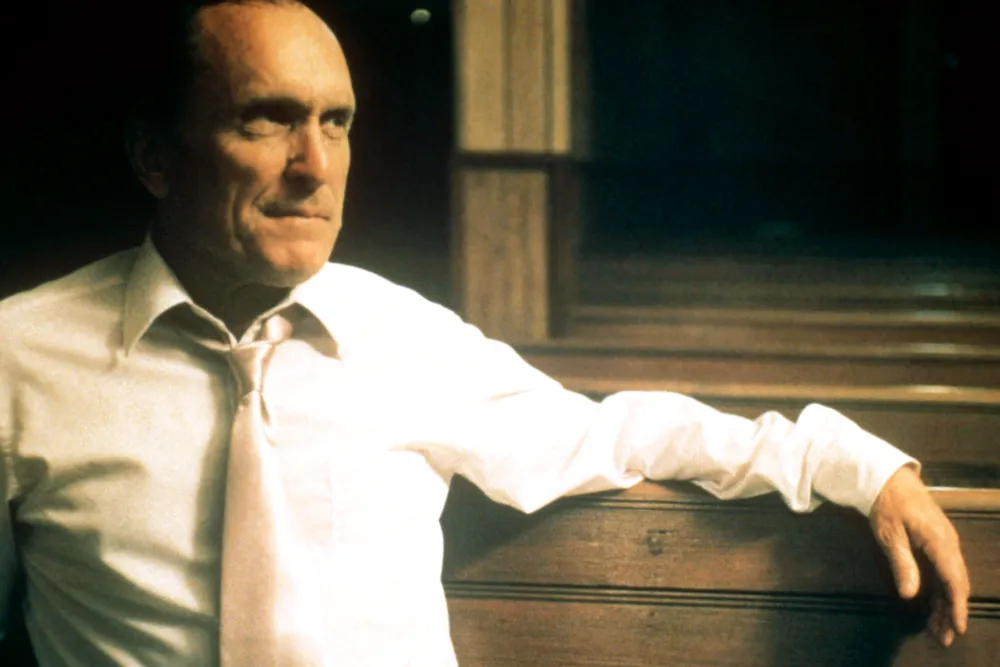

Yet as memorable as he was playing Tom Hagen as an insider who remained, somehow, on the outside, Duvall was also biding his time, waiting to show audiences everything he could do. In “Network” (1976), as the profit-hungry executive vice president of the UBS TV network, he let loose in a new way, as in the outrageous moment when Howard Beale’s crazed TV show first tastes success, and Duvall’s Frank exclaims, with reckless glee, “It’s a big, fat big-titted hit!” This was the other side of Duvall: the showman boiling over with bluster, the amoral life of the party, with a grin as wide as a shark’s. So here was the grand paradox, and the real meaning of Duvall’s range. Few could portray a courtly gentleman as convincingly as he did; he could embody the soul of decency. Yet he was also driven to explore the dark side, and he did so as profoundly as any actor of the last half century.

In 1979, he did it in two extraordinary ways. In “The Great Santini,” Duvall gave what felt at the time – and still does – like the defining performance as a father who cripples his children with the harshness of his demands. We’ve seen this kind of movie so often now that it’s a genre unto itself. But Duvall still owns it; his “Bull” Meechum is a hypnotically layered hard-ass who’s a destructive father yet can never be written off as a villain. Duvall’s understanding of him is too rich. And in “Apocalypse Now,” Duvall, as the surf-happy, bare-chested, U.S. Cavalry-hatted Vietnam officer Lt. Col. Kilgore, let loose with a memorable maniac of a character who was so gloriously satirical and, at the same time, so vividly real that he gave Francis Ford Coppola’s movie a huge swatch of its meaning. Duvall’s delivery of the line “I love the smell of napalm in the morning. It smells like…victory” made it the deadly funny swan song of America’s imperial reign of military might. (It’s not that we didn’t try again; it’s that Duvall’s portrayal of lock-jawed insanity showed you why it would no longer work.)

And after that, Duvall was just getting started. Going forward, his performances would now make a point of drawing on both sides of the duality. That’s why he won the Oscar for best actor in “Tender Mercies” (1983): His Mac Sledge was a taciturn recovering alcoholic who spent the entire movie trying to straighten up and fly right, but what made the performance great was its haunted undercurrent — the hint, communicated by Duvall between the lines, of all the bad places that Mac had been. You could feel that same richness, that ripe moral ripple of a man teetering between being a knight and a scoundrel, in the L.A. police drama “Colors” (1988) and in “Lonesome Dove,” the 1989 TV Western miniseries that allowed Duvall to give one of his most expansive performances.

And his greatest performance? To me, it’s the one Duvall gives in “The Apostle,” the 1997 drama he also directed. The movie is one of the authentic masterpieces of the independent-film era, and it contains, quite simply, one of the greatest pieces of screen acting you will ever see. Duvall plays “Sonny” Dewey, a local rock star of a Pentecostal preacher who occupies a position of extreme power in his Texas church. He’s a deeply religious man; he’s also a narcissist who lives for his own gratification. That’s why his wife (played by Farrah Fawcett) has begun an affair with a younger minister, and is trying to depose him at the church. At a Bible-camp softball game, Sonny picks a fight with the minister and ends up tapping him on the head with a baseball bat.

It is not the most violent of smashes. Yet in that very ambiguity, the question is raised: How violent is this man of God? Is he merely angry, or is he homicidal? Duvall is really asking: What, deep down, is in his heart? In all our hearts? And that’s the question Duvall asked throughout his career. “The Apostle” is a character study in which we watch the sacred and the profane, the worship of God and the worship of the self, battle it out in one man’s soul. Sonny escapes the law and sets up a new church, and as he begins to preach in that church, the words pouring out of him as if he were an auctioneer speaking in tongues, Duvall’s performance becomes nearly symphonic. The film is so staggering, so moving, that by the end you feel floored. What Duvall has shown you is the full range of what a human being is.

+ There are no comments

Add yours